I only know how much I get paid, the rest...

- Aitor González

- Re estimando , Statistics

- January 20, 2025

Definitions matter as much as the outcomes themselves. Because… What happens when those outcomes directly affect people’s wallets? This is where the each one’s fire really comes to the surface and burns even a mother if need to. When we have to make certain statistical readings to understand a situation, we must pay more attention even to the context of the numbers than to the numbers themselves. This is where statistics becomes a battleground, and experimental design a weapon loaded with legal, ethical and economic implications. Ideas before numbers.

Playing with math is relatively easy and the impact and interpretation is immediately understood. On any given problem, when analysed with a mean or median, our conclusions about the study population change. It changes the narrative. Completely. This is in fact ‘intuitive’ and very quickly apparent. It is intuitive precisely because the definitions of mean and median are well defined and accepted. It is not for nothing that there are ’numbers’ people. People who do not ride contradictions.

It gets much more complicated when you play with the definition of the numbers to be used in the calculations. If manipulating the calculations changes the story, manipulating the definitions changes the entire paradigm.

Tip

This project can continue thanks to our patrons. If you also want to collaborate you can do it here .

A sandbox example:

Consider a company with 100 employees, including 3 directors. The company is located in a region where the average cost of living is around €20,000.

The end of the financial year is approaching and it is time to do the maths. The company itself has not done badly. But there is a lot of discontent. The employees, organised in unions, report that their salaries are not enough to cover the basics, while the company generates very high profits. The headlines spread like wildfire: ‘Evil company accused of enslaving employees’. Protests begin to threaten the company’s image.

Board of directors crunches the numbers:

- Profit: €750,000 to be split between 3; €250,000 for each director.

- Directives salary: €50,000 per director (3 directors).

- Salary for each employee: €15,500 per employee (97 employees).

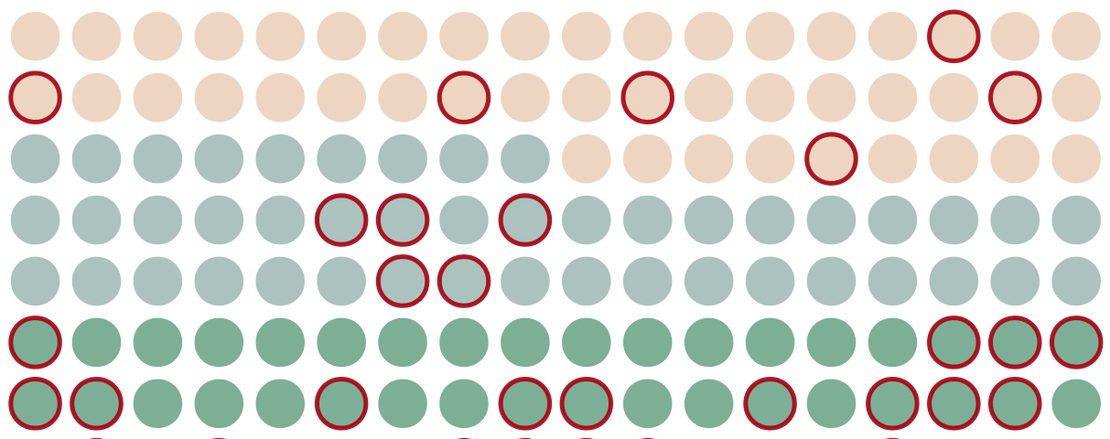

How much is the total salary paid? A simple weighted average will tell; 3 directors and 97 employees.

weighted.mean(c(50000,15500),c(3,97))

[1] 16535

The company reports in official figures an average salary of €16,535. This is a problem for the public eye, as the salary paid by the company does not cover the €20,000 cost of living for employees located in the company’s region. All this, remembering that the directors take a total of €300,000 in profits.

The press and the major labour unions attack with the argument that the average wage does not cover the region’s expenses. They are absolutely right, but they make a mistake. They rely solely on the company’s own reported figure being correct. They don’t care about that definition. The company realises this and they play their card trick.

As they are only being attacked by the average wage, they decide to change the compensation form. Benefits are now paid as part of the directors’ salaries. This kills two birds with one stone: they lower the benefits and increase the average salary on top of that, whitening their image.

They will not be able to put all the profits into the directors’ salaries, as some things cannot be done legally, but the magic of fiscal engineering will make most of the transfer possible.

Board of directors crunches the numbers again with “fiscal magic”:

- Profit: €33,333 for each director. Now only €100,000 in total.

- Directives salary: €266,666 in total (€50,000 original + €216,666 ‘profit’).

- Salary of each employee: €15,500 per employee. They leave it exactly the same.

(750000-100000)/3

[1] 216666.7

How much is now the new total wage paid? Again with the weighted average:

weighted.mean(c(266666,15500),c(3,97))

[1] 23034.98

What a pleasant surprise. An average worker now earns €23,034. The narrative now is that the company has had very low profits, and that it is looking out for its employees, has raised the average wage to the point where all employees are now paid more and that there may be turbulence in times to come, so we can take advantage and lay off staff who do not meet the criteria to maximise even more profits. What could they complain about?

By changing the narrative through numbers, the company has removed the big brother who sees all and judges all. Numbers, the champions of objectivity, are nothing more than abstractions of people’s ideas.

When the example comes to life

But hey! It’s all laughs and procrastination in isolated examples without context. So let’s put some reality into the matter, while saving certain differences.

In the 1990s, Nike was in a period of great global expansion, establishing itself as one of the leading brands in the sports industry.

Nike, like other major global brands, implemented a production model based on outsourcing. Nike outsourced production to factories in developing countries, where labour costs were considerably lower.

Moving production always leaves dissatisfaction, especially for a global brand with high visibility. Nike faced the risk of various types of criticism, both economic from the abandoned locations and ethical in its global supply chain. In order to protect its image, Nike demanded that its subcontracted factories meet certain standards.

Among these standards was meeting decent worker pay, but keeping costs extremely low. Nike negotiated very tight prices for products, leaving factories with ‘minimal’ profit margins. However, fierce competition among suppliers was unleashed. Foreign factories, especially in Vietnam and Thailand, competed with each other for Nike contracts.

Nike’s strategy seemed perfect. Not only did it whitewash its image in the eyes of the public, avoiding accusations of exploitation by ensuring that it maintained ‘living wages’, but it also avoided the emergence of strong competition by leaving very low profit margins to the franchised companies. However, of course, Nike was not the only one with ‘big ideas’. As they say, for every law there is a loophole.

Many of the factories subcontracted by Nike relied on malpractice to meet standards and gain the favour of being Nike franchises. One of the most common was the manipulation of wage reports. In order to appear to meet labour standards for worker wages, factories inflated wage averages. This distorted the metrics as wage categories were mixed up in the calculations. Managers, supervisors and administrative staff, whose wages were significantly higher than those of production line workers, were counted in the average wage calculations.

This way, the factories were ‘making up’ the figures, maintaining the narrative that their core workers were very well paid, when the reality was that wages for workers were extremely low, often insufficient to cover even basic needs in developing countries.

Moreover, audits by Nike or local authorities rarely detected these manipulations. Inspections were often sporadic or superficial, and factories knew how to prepare themselves to appear compliant. Even in countries with stricter labour laws, corruption and lack of effective regulation helped perpetuate these practices.

Behind this system, factory workers were trapped in exploitative working conditions. Low wages, long hours, unsafe working environments and a lack of union representation were the standard. This model not only revealed the structural flaws of the industry, but also demonstrated how large global corporations could profit from a system that privileged profit margins over workers’ welfare.

In the end, several organisations echoed the facts. The NGO Oxfam, in its article [‘Sweatshop wages and unpaid care work’] (https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/sweatshop-wages-and-unpaid-care-work-double-burden-asias-women-its-economy-booms ‘Oxfam article’), exposed in detail the precarious working conditions in subcontracted factories, highlighting the manipulation of wage reports. Their research, along with campaigns by other organisations such as Global Exchange, helped to make these practices visible and generate significant public pressure on Nike.

The actions were successful, and Nike finally decided to rethink its labour model and policies. In particular, it strengthened audits and outsourced the process in order to maintain rigorous control of compliance.

However, the Nike case in the 1990s remains an emblematic example of the ethical and social dilemmas of what manipulation in the calculation of a figure such as a salary can involve.